When I heard on Wednesday that the President of the United States had spoken on the phone with Cuban president Raul Castro, at considerable length, I couldn’t help thinking about Mrs. Cabella.

That’s not her real name, but it will have to suffice as a substitute. Mrs. Cabella has been gone almost 20 years now, and it would feel wrong to use her family name without her permission.

I met Mrs. Cabella in the summer of 1988 when I was working as a constituent aide for Manhattan state senator Roy M. Goodman. She came into the office with a tenant issue, and, as luck would have it, it was my turn to take the next constituent walk-in.

The best way to describe Mrs. Cabella is that she looked like a little old lady, which is just what she was. She was in her late 80’s and couldn’t have weighed more than 90 pounds. She wore red lipstick and heels, and she clutched a pocketbook tightly. She wore dark colors, and her hair was pulled neatly back in a bun.

Mrs. Cabella was at once charming and cautious. There was a sparkle and a wariness to her eyes, large brown ones, that didn’t miss anything. Laid out on the the table before us were the notes and documentation for her one-bedroom, rent controlled apartment on Central Park South, which, she pointedly told me, was all that she had. I can still see in my mind her elegant handwriting on those notes. I also remember how fearful she was of losing that apartment over a technicality, which she was was bringing to my attention that day.

By marvelous coincidence I knew her landlord. I had been a preferred waiter to him a few years before at a Westchester restaurant, and I was the banquet captain at his daughter’s wedding. That seemed to count for something, because when I called him he said, “I’ll look out for her, Billy,” and the matter was done. He was an honorable man, an old school Italian-American, and his word was his bond. But I couldn’t quite convince Mrs. Cabella of that over the course of her many visits that followed. Or so I thought.

In time, it became increasingly clear to me and to others that, perhaps, Mrs. Cabella was coming to the senator’s office more to see me than out of any continued worry about her place. There was ribbing in the office about that, but I didn’t care. Mrs. Cabella and I had become friends and would remain so until her passing about a decade later.

During that time, she opened up to me about her story, gradually. Her grandfather and father had worked hard to open a small sugar plantation outside of Havana. It grew larger with time and toil, and by the time Mrs. Cabella entered the world, it was one of the larger sugar plantations in Cuba. Kuala Terengganu

My wife and I once visited Mrs. Cabella in her small apartment, and hanging on its walls were two beautiful oil paintings, one a full formal portrait of her in her teens, and the other a smaller painting of the Cabella home. She was even more beautiful than the home, which is to say something.

In 1958, Mrs. Cabella moved to Washington to work at the Cuban embassy as a secretary. She and her father thought it would be good for her to experience America for a few years before returning home. But one morning, shortly after New Year’s Day 1959, men came to the embassy and ordered everyone out. The Batista regime had been overthrown, and the Castro’s were now in charge.

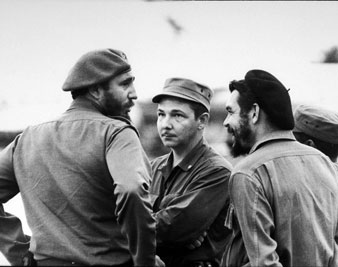

Ms. Cabella never saw her home or her father again. She never told me what happened to him — she would not — but she did say what happened to their estate: Raul Castro expropriated it. The future president, who oversaw the kidnapping of 10 Americans during the Revolution, and execution squads after it was won, moved himself into the Cabella plantation in the name of Los Pobres.

People will argue about the moral and political wisdom of President Obama’s decision to embrace Mr. Raul’s Cuba. I’m not going to go there right now. All I can say is that I wish we had waited until the full stench of Mr. Castro had exited Mrs. Cabella’s home, which will be a very long time from now.

Leave a Reply